Document Author(s):

Year Published:

Topics:

Tags:

SRLN Brief: Evolution of Court Staffing for SRLs (2019)

Over the last fifteen years, leaders from the courts, legal aid programs, private bar associations, and allied professionals have actively pursued innovations to reimagine and redesign the civil legal system so that access to justice is a reality for the millions of people without lawyers who pass through the more than 15,000 state and local courts in America.

It is estimated that at least 3 out of every 5 people in the civil cases involving private individuals have no legal representation. Called self-represented litigants (SRLs), these people come from all walks of life. SRLs are filing for divorce or custody, seeking child support, defending against corporate creditors, seeking domestic violence protective orders, probating their loved one’s estates, and seeking guardianship for an incapacitated child or aging parent. Nearly 10% of Americans seek relief from the courts every year. Almost all of them do so without the assistance of an attorney while facing an often complex and opaque system. (See SRLN Brief: How Many SRLs (2019).)

With the leadership of the Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ) and Conference of State Court Administrators (COSCA) a blueprint for change emerged in 2002 when the Conferences passed their first resolution to inspire leaders to take action: In Support of a Leadership Role for CCJ and COSCA in the Development, Implementation and Coordination of Assistance Programs for the Self-Represented. This resolution was supported by two prescient and comprehensive white papers written in 2000 and 2002 that continue to be as relevant today as when written.

The first court self-help center was opened in 1994 in Maricopa County, Arizona. By 2006 there were more than 150 centers operating in twenty-six states, and more than 250 nationwide by 2014. Preliminary results from SRLN’s national survey of self-help services, suggests that all states now have a minimal level of self-help to include basic forms, with most providing some level of individualized assistance.

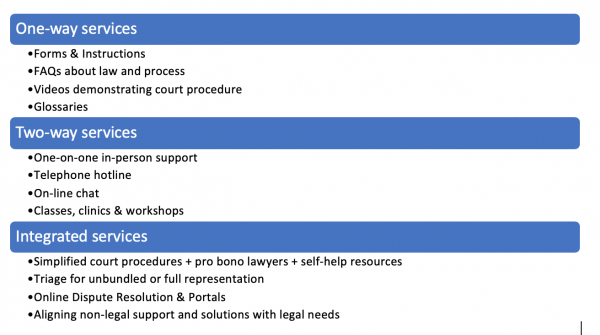

Court self-help clusters into three categories of assistance, which can be broadly described as follows:

As court self-help services have matured, the roles and training of who provides help have also evolved.

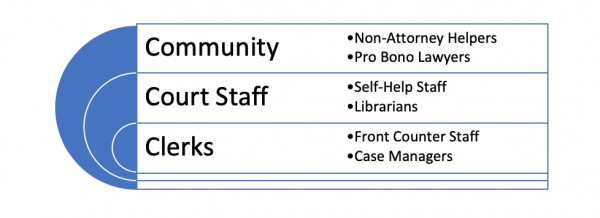

Historically, the sole point of entry for the public into the courts was the clerk’s office. Early self-help focused on developing a framework for clerk staff, who previously had been trained to interact with mostly lawyers, to provide procedural information to the public.

As courts learned that neutral and impartial coaching was effective in helping the public better navigate their court cases, self-help centers with specially trained attorney and non-attorney court staff emerged. Many courts also engaged the law libraries that were well equipped to offer resources, expertise in helping the public, and the physical space for the public to work. Concomitant with the expansion of court staff roles was the rise of technology and web-based solutions. Combined, these changes allowed the public to access court through a variety entry points: the clerk’s office, the self-help center, the law library, and on-line.

These innovations in staff roles and resources have made significant contributions to ensuring the courts provide appropriate access to the public. However the complexity of legal matters coupled with the emotional distress caused by such matters means that the public demand for services and support still largely outstrips the capacity of courts to respond without further expansion of staff capacity. Unfortunately, court budgets are notoriously underfunded, so there is often little chance of a direct legislative appropriation to support SRL services. However, one particularly promising innovation in recent years to address this crisis in capacity is the courts’ engagement of non-lawyers who are trained specifically to support self-represented litigants. These non-lawyer roles include augmentation of self-help staff to offer one-on-one help in forms completion, information and referral, and targeted support in the courtroom. They serve to significantly amplify the resources of the courts to meet the needs of self-represented litigant, and offer a community based resource pipeline with significant untapped capacity beyond the traditional legal community.

Evolution of Court Staffing

As the access to justice movement has grown more broadly, there is a growing understanding that collaborative partnerships among traditional and non-traditional stakeholders are necessary to deliver appropriate, effective and sustainable services. In addition to providing needed resources to the courts, the expansion of non-lawyer roles in supporting self-represented litigants is likely to produce new relationships and strategies, both in courts and communities, to leverage new resources that will be significant elements in providing justice for all.